A "Colossal Concern" : Touring Cuba City's Sulphuric Acid Plant

One hundred years ago, a reporter from the Dubuque Times-Journal visited the National Zinc Separating Company's sulphuric acid plant, remembered by many today as the "Roaster," located southeast of Cuba City. What resulted was the article below, which is essentially a detailed tour of the enterprise. The reporter found the plant to be well worth the trip and encouraged readers to visit, as well. The narrative can be difficult to follow (at least for me!), but it is priceless to have.

|

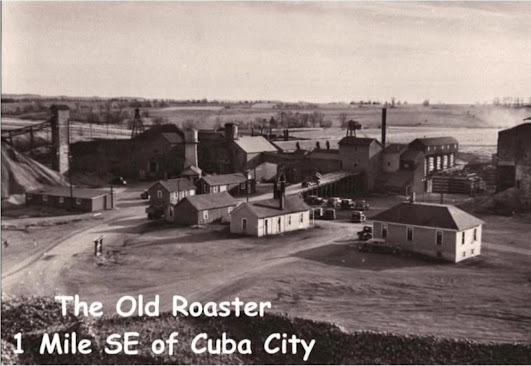

| The Roaster was located off of Roaster Road, where Wiederholt Enterprises is today. This image is from the "Remember When" DVD put together by Beanie Loeffelholz and the City of Presidents. |

Four years ago the hand of war stretched across the sea, touched America and was off, its purpose being accomplished through the entry of the United States in the world turmoil. In its wake, it has left monuments in every hamlet, the land over, to the god of war, Mars. But those monuments have fast settled back to peaceful pursuits, forsaking the banner of the war god.

Such is the case of the National Zinc Separating company, with a 160-acre stretch of land and a plant covering 40 acres at Cuba City, Wis., a short hour’s ride from Dubuque. A subsidiary of the Steel & Tube company of America, the plant to date represents an investment of over $1,000,000.

In 1918 the government had taken the plant over and were building, from an appropriation of $800,000, refineries and acid making machines for the purpose of procuring the prized oleum, or fuming acid, for munitions manufacture. The work was rushed. Practically everything was subjugated to the completion of the plant and the manufacture of the prized substance from the raw zinc ores of the Wisconsin mines.

Reclaim Waste Land

In consequence, the country for miles around was denuded of vegetation from the sulphur gases that were allowed to escape into the air as waste. Today, as a result of certain processes to reclaim the gases and make liquid sulphuric acid, the fields are verdure clad and trees and flowers abound about the plant. The National Zinc Separating company since being taken over by the Steel & Tube company of America has instituted many reforms, including the cultivation of several hundred of acres near the plant to demonstrate conclusively that the plant does not harm the soil when wastes, now by-products, are properly taken care of.

Situated a half mile from the beautiful town of Cuba City, Wis., the plant can be seen for several miles as it is situated in a little valley. Everything about the plant is quiet, but the thin wafer like wraith of smoke emanating from the tall stacks and towers belies the quietness.

Inside the plant, a series of seven buildings grouped together, one is impressed with the colossal proportions of the plant, combining as it does a refinery for the reduction of ores and their separation from mass and the utilization of waste gases for the manufacture of liquid sulphuric acid. Only 80 men are required to take care of the million dollar plant, working in shifts of eight hours.

“Start operations at one end and the other will take care of itself,” was the terse comment of the guide.

Provide Homes for Men

Leading to the plant along the county road, and situated several blocks away, are workmen’s homes, provided by the company. Standing, silent and vacant, but symbolical of the rush that was seen in 1918 when war was at its height is the construction camp. It is no longer used.

Facing roaster ovens and acid sheds are rows of little bungalows on the plant site proper. Some are for offices and still others for laboratory purposes. The latter are taboo to all visitors on account of experiments now being conducted with a view to the utilization of iron-sulphur ore used to make sulphuric acid after the zinc has been refined from the raw materials, as another product.

Superintendent E. G. Duetman [Deutman], in charge of the plant, is the first person to be met upon entry to the office. Without him, a survey of the plant is impossible, as the various processes, while not intricate, are hard to explain to those not acquainted with work of this character. General Manager W. M. Smith of Platteville, Wis., is usually occupied with field work and can rarely be found at the plant.

Scene About the Plant

Standing on the porch of the bungalow office that seemed a bit homey in the desolation around the plant proper, with not a blade of grass or branched tree, a quick survey of the 160-acre tract was impossible. Everywhere storage sheds, with huge piles of iron-sulphur ore, a by-product remaining after the refining of the mine ore for zinc, has been completed are to be seen. Another mental picture was a stretch of cultivated field close to the plant, just beginning to show green where the seeding oats had begun to peep. The houses of plant workers loomed in the distance.

In the foreground is the electrical building with its black smokestack rearing 145 feet skyward. It also contains transformers and a water-pumping plant capable of supplying enough for plant and fire purposes. Over 400 gallons of water a minute are pumped and used in the cooling of gases.

Annually, the plant turns out 75,000 tons of zinc refined from crude ore. From the gas by-product, through a new process in operation only a short time, from 18,000 to 20,000 tons of sulphuric acid are manufactured. A roaster, designed to utilize the gases to be obtained from the iron-sulphur ore, a residue after the zinc has been extracted, is completed, has been tested and found a success. It will be placed in operation as soon as markets pick up.

Utilize Nearly All Ore

Through the discovery practically every bit of ore taken from a mine with the exception of a small residue will be utilized. After all gas has been extracted from the iron-sulphur ore the iron ore can be treated by a special process and made commercially profitable.

Started in 1911 and added to until the present million dollar plant stands as a monument to the furtherance of chemical science, changes are being made from day to day as experiments determine the need of feasibility.

Going through the plant one is confronted with wonders at every turn. The first step in the reduction process is the receiving of the ore. The company maintains its own siding and spurs. More than 2,000 feet of track are on the plant area.

Bins for the ore will store 1,500 tons, while cars received from the Utah mine at Livingston; North Unity at Hazel Green; Nightingale at Lead Mine, and Connecting Link at Jenkinsville in Wisconsin are unloaded at the rate of a ton a minute.

Ores mined in Wisconsin are usually found associated with a blend of pyrite and marcasite. Owing to the unusually high iron content, smelter work is not suitable and the treating through roasting and magnetic separation is resorted to. The raw material received varies greatly in mineral content, being composed of zinc, iron, lead, lime and sulphur in different quantitities.

Seven Hearth Furnaces

Methods of roasting the ore to extract the zinc metal, sulphur ore, and sulphur gas are practically the same. A seven hearth furnace, wedge shape, is the most common. The general treatment of ore consists of roasting it, cooling it, and then separating it by magnetism. The furnace occupies a large building and is over 22 feet in diameter and 24 feet above the floor.

It is a riveted shell of steel, made fireproof by bricking. Special shaped fire brick is used for the hearths, each hearth forming an arch above the one below. A central shaft of hollow steel insulated against fire and heat and open at the top and bottom revolves arms attached to it and works the ore to successive levels.

The shaft is open at top and bottom and the air draft through it keeps it sufficiently cool for workmen to enter. Inside the center of the shaft may be termed a living hell for on all sides is seething metal heated to 900 degrees centigrade. Liquid, molten, living fire, hardly describes the interior of the retort.

When one sees the vent of the furnace, the size of a dollar, opened, it is instinctively to draw back as the livid heat strikes one’s face and the fumes of the sulphur gas begin to be felt. When once ablaze, no further attention to fires need to be paid except to regulate air drafts on the melting ore. The heat and gases of the mass, when once ignited, keep it burning so long as supplies of ore are added to the roaster.

At the top of the roaster two hoppers keep feeding the ore automatically. It is worked to the central shaft and is progressed to the lowest, or seventh hearth, where it is discharged into two rotary coolers. The maximum heat is 900 degrees centigrade reached by the ore at the lowest level.

After passing through the furnace the ore is then ready for separation. Four rotary drums are used to cool the ore. Sprays directly above the drums play on the ore as it passes through the drums and cools it. It is then ready for separation by the magnetic process.

The ore already cooled is passed over a rougher machine, and shaking table. Magnets are above the table and under them a revolving aluminum spider with other magnets. It is by this means that the zinc is separated from the sulphur-iron ore. The former goes to the shipping bins, while the latter travels to an outside dump by means of bucket hoists to await further reduction for sulphur acid and iron ore.

Coming back to the gases still in the roaster. Up until a year ago these gases from which sulphuric acid, a valuable commercial by-product used in many industries is made were allowed to pollute the air and destroy vegetation for some distance about the plant. Now they are utilized. A visitor to the plant can hardly detect the sulphuric acid odor unless nearby the reduction machines.

From the furnaces the gases are passed through a dust chamber and thence to what is known as a cottrell precipitrator. Here a phenomena unexplainable to chemical science asserts itself. Through the introduction of electric wires carrying 65,000 volts of electricity through the gas pipes the majority of the dust remaining in the gas is precipitated into specially built hoppers.

A huge rotary blower fan then pulls the gas from the precipitrator over to zinc lined washing tanks. The gas is forced upward and out of vents at the top of the tank, while water is sprayed downward and through the gas tending to still further clean it and remove dust.

Here miles of pipes are seen used for cooling the gases before it is washed and filtered more. The gas to be usable must be absolutely pure and clean. Five miles of pipe, the majority of which is lead, are used in the plant constantly. Everywhere one looks nothing but long rows of pipes are to be seen.

After the gases pass through two series of row upon row of pipes with water falling from them in miniature cascades, they are inducted into coke boxes containing tons of the purifier and lined throughout with zinc. They pass through a series of three such boxes.

For Final Purification

The gases, not yet clean, is then passed through a sulphuric acid bath in two acid shower towers. They then are filtered through ten mineral wool filters. Removing one of these filter caps packed tight as big as a room, the packed in mineral wool is seen coated with a fine residue of red dust. The blower fan up to this point has been puling the gas. Two huge pumps then take up the work and force the gas onward in the last lap of its journey towards sulphuric acid.

Another phenomena unaccounted for and as yet unexplainable occurs here, with the aid of $50,000 worth of platinum. The gas is again heated at 450 degrees centigrade. It is then inducted into four converters composed of magnesium sulphate impregnated with particles of the $50,000 worth of platinum so small that the eye cannot see them.

The gas has up to this point been known as sulphur dioxide. When it comes from the convertors it is known as sulphur trioxide, an altogether different substance. The gas is passed through the final set of coolers. The gas then comes to the tank shed, wherein are hundreds of large cylindrical tanks for the storage of the sulphuric liquid acid after it is changed from gas to liquid.

The gas is built up gradually and as fast as it attains a strength of 98 degrees it is diluted to make way for the remainder coming along the line.

Can Store 2,000 Tons

Storage tanks provide facilities for the storage of over 2,000 tons of the product. Twenty cars are used to transport the acid which is used in the manufacture of fertilizers, leather, glue, paint, refining of metals, and innumerable other business enterprises.

Still another roaster, although of a different type than that used to refine the zinc has been erected. It will refine gas exclusively and prepare the iron for further commercial uses. This waste product to date has been useless and commercially valueless. Discoveries made at the plant and processes perfected will make it a wonderful find.

Dubuque has within easy reach a wonder place for those who would see in actual operation, a plant such has been described. It is well worth the trip, for it again tells the story of striving and forever perfecting in the hope of the ideal. With the aid of Mars, God of war, an industry near Dubuque, has triumphed once again.

--Dubuque Times-Journal (May 15, 1921)

Comments

Post a Comment